The son of immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Eric Bueno represents the first generation in his family to go to college, but the computer science degree he earned at the University of Connecticut last year has turned out to be just the beginning of what he’s on his way to accomplishing in higher education. Now his sights are set on a PhD and becoming the kind of mentor who has helped him along the way.

“Growing up in the Hartford school district taught me how to make a lot with a little,” Bueno said.

“That was a way to get students some college experience because being first generation you don’t really get that kind of direction from say, your parents or your siblings,” Bueno said. “That’s where I realized I wanted to continue going to school after high school.

“Now I’m hoping to pursue a PhD.”

Bueno committed himself to pursuing a doctorate earlier this summer as he reached the midpoint of his two-year term in the Research Scholars Program (RSP), a post-baccalaureate opportunity in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences (BCS) at MIT. The program, jointly funded by The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, BCS, K. Lisa Yang, and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, is designed to provide outstanding recent college graduates from historically underrepresented minority groups and/or economically disadvantaged backgrounds with additional academic training, as they earn a full graduate-level stipend, to become competitive PhD applicants. Right now five scholars, including Bueno, are in BCS labs. Another group of five will be joining the department soon, including two Picower labs.

Bueno is working with Picower Institute investigator Steven Flavell, who studies how the nervous system produces long-lasting but flexible internal and behavioral states. Bueno said he has gained very valuable research experience applying his computer science skills to cutting edge problems in neurobiology. That has helped inspire him to continue exploring the power of computer vision in biomedical research as a graduate student next year.

Barcoding cells

Bueno originally studied cybersecurity at UConn but began to realize that a more fulfilling way to help people could be to apply his technological talents in biomedicine. To explore this, he earned a summer research position in the Broad Institute lab of Schmidt Fellow Juan Caciedo, which uses artificial intelligence to improve analysis of microscope images. A friend he made in the Broad Summer Research Program told him about the RSP opportunity around the corner in MIT’s BCS department, which could provide a new place to pursue these interests after graduation.

At MIT, Bueno met Flavell, who has been seeking a way to reliably track the activity of every one of the 190 or so neurons in the brains of C. elegans worms as they freely move around and behave for minutes or even hours at a time. Such rigorous tracking will require advanced computer vision techniques -- it’s a fiendishly difficult problem to make a system that will reliably distinguish each cell, every fraction of a second, no matter where and how the worm moves.

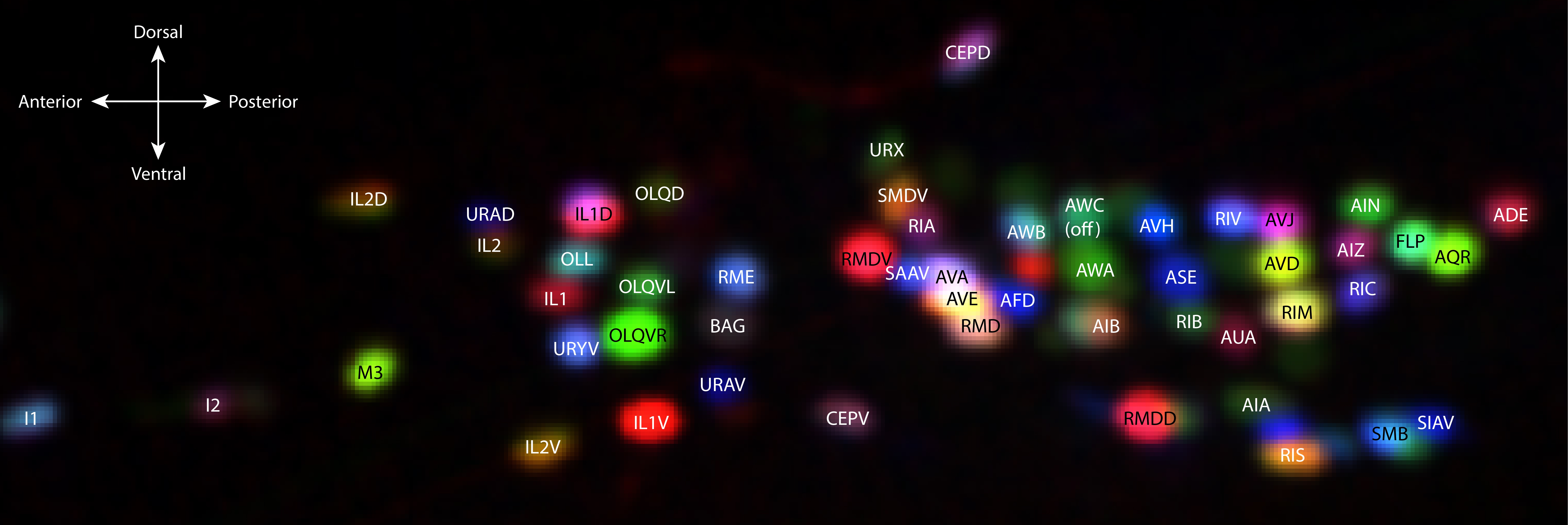

They might have the solution. The lab is working with a strain of worms engineered by the Columbia University lab of Oliver Hobert in which each neuron can fluoresce with a unique combination of three different colors—akin to the red, blue, and green that make up each pixel on a computer or phone screen. Ultimately, as in those pixels, when relative levels of those colors are combined they compose a unique hue, and therefore a unique color “barcode” for each cell. The Flavell lab is doing some extra engineering to use this strain in experiments where the worms can continue to exhibit a full range of behaviors.

“The unique angle we bring [is] that we record the majority of neurons in the head while the animal is freely moving and then immobilize the animals in order to label the individual cells,” Bueno said. “Most work with whole-brain imaging in C. elegans either immobilizes the animals for the duration of the experiment or simply doesn't track as many cells as we do if they're moving.”

Determining how the defined neurons across the C. elegans brain change activity during free behavior is allowing the Flavell lab to gain fundamental insights into how the nervous system generates behavior.

Before the computer can reliably associate each barcode with each cell in a moving animal, Bueno is working to do so manually, creating a reference set of images that can teach the computer. Along the way, he’s making it easier for the machine, for instance by writing code that corrects each image to account for bleaching caused by the lasers that make the fluorescent effect occur, and warping (or, registering) the images so that they can all be aligned.

“We have been extremely fortunate to have Eric in the lab,” Flavell said. “Eric came to us with extensive computational skills and intellect, and he has applied those tools wonderfully to neuroscience. He developed an approach to fluorescently barcode the neurons that we record throughout the brain while animals are freely moving. This allows us to relate brain wide neural activity to the exact positions of neurons in a wiring diagram. This is just about the first data of its kind.

“It is challenging to run all of the complex image analysis tools and labeling strategies needed to pull this off, but Eric has an extraordinary ability to put this all together.”

Over the next year, Flavell said, as Bueno gets the system up and running he will be central to the lab’s efforts to analyze the data it generates.

Paying it forward

Coming to MIT wasn’t easy for Bueno. Despite its proximity to Hartford, he hadn’t been to Boston until his sophomore year at UConn and MIT’s global renown can also make it a bit intimidating, he said.

“I still kind of wake up sometimes and don’t believe that I am here working at MIT,” he said.

But getting together regularly with his fellow RSP members has helped him feel like he has a home here. With some shared circumstances and outlooks, the group clicked almost instantly, he said. Adding to the sense of belonging, he said, are the reassurances and advocacy provided by program mentors Josh McDermott, associate professor in BCS, and Mandana Sassanfar, an MIT lecturer who leads diversity and outreach for BCS and the Department of Biology.

Bueno said he’d love to end up doing something like what Sassanfar does after graduate school. He’s already had some experience mentoring: As a UConn student he volunteered to teach in the UCAP program and reveled in seeing students light up upon reaching an “aha moment” after struggling with a concept.

“I'm a product of so many different mentors throughout my life,” Bueno said. “I've seen a lot of people kind of go down different paths that may not be the best choices. I could have very easily been one.

“Having been raised in Hartford, where I would say you can really go either way, it just taught me the importance of having that kind of figure who can kind of help you figure out what was important to you and how you can find that in a really constructive way.”

Today he’s gaining skills, knowledge, experience and mentoring in the RSP. Tomorrow he might be providing all those things for a next generation of scholars.