Adults can learn and remember, so it’s clear that even a mature brain is capable of changing with experience (an essential and marvelous property called “plasticity”). Still, in the early 2000s neuroscientists were struggling to find direct evidence that neurons in the adult brain exhibited any of the reshaping or connection changes that such functional flexibility should require. Compared with developing brains, adult ones appeared fixed and hardwired.

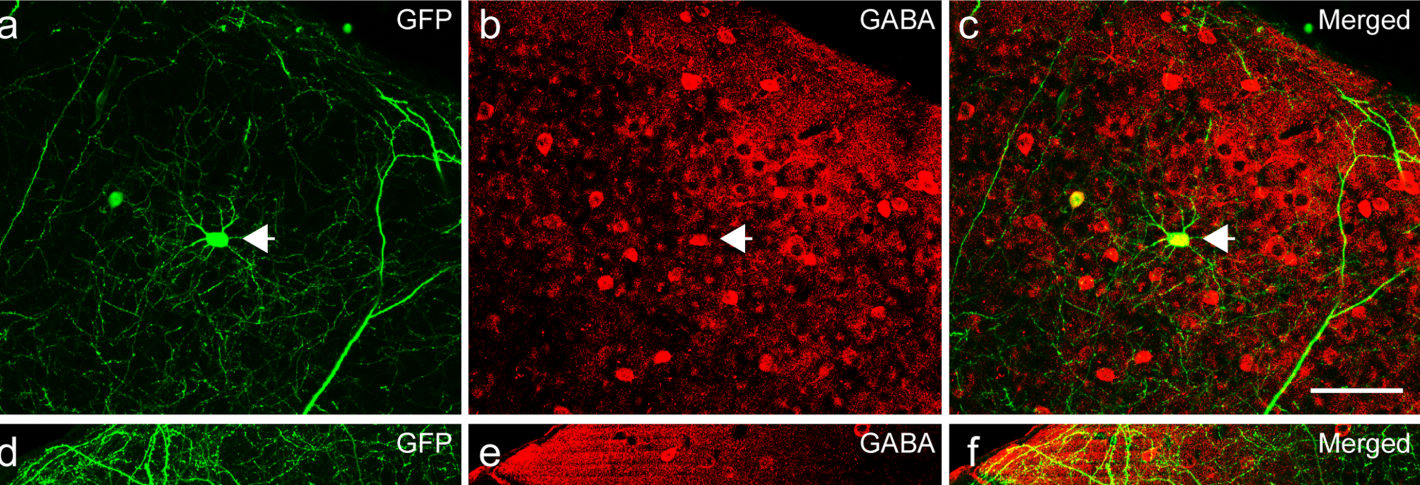

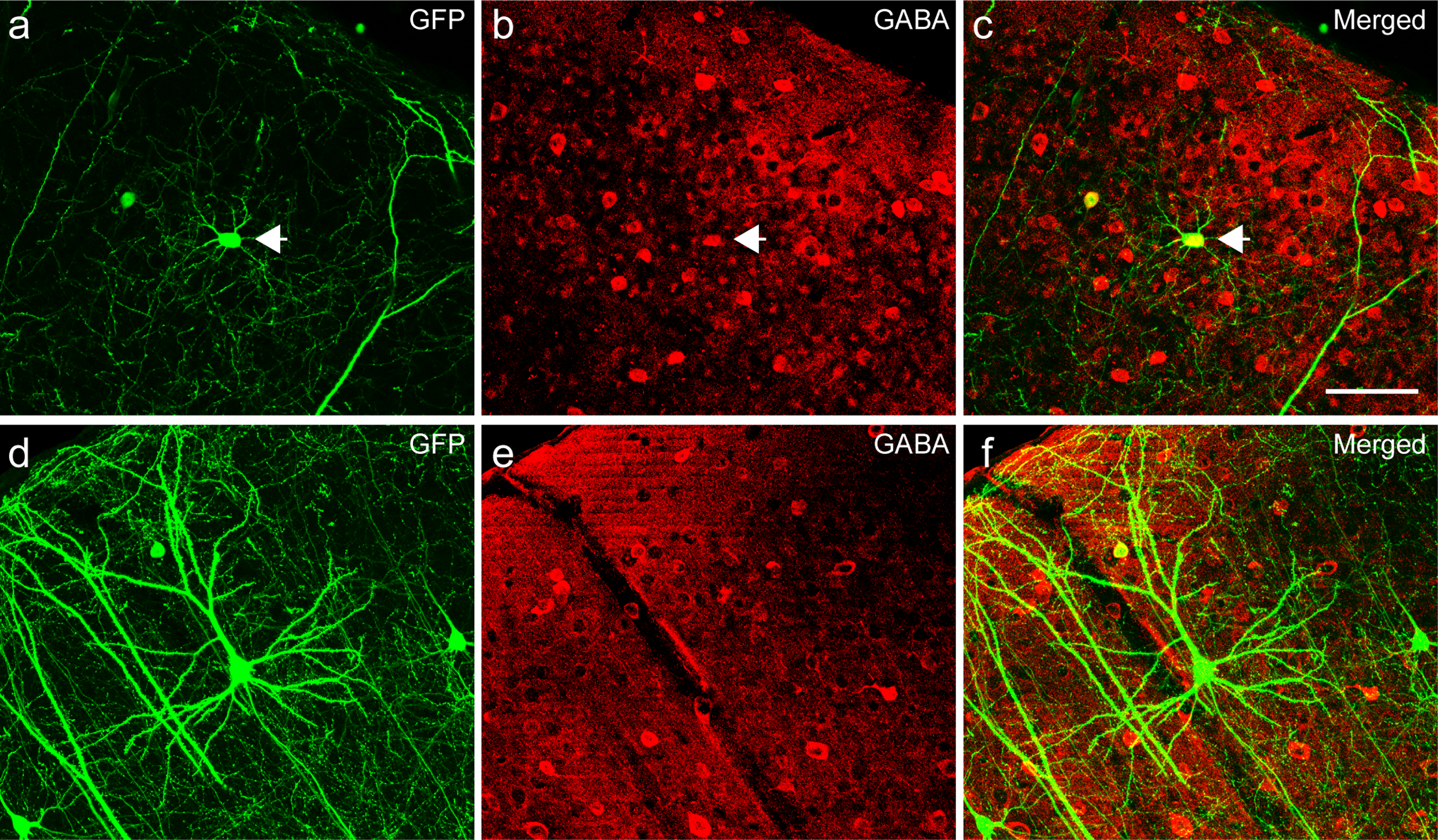

In 2006 a collaboration led by Elly Nedivi’s lab made the breakthrough, becoming the first to directly and unambiguously show that neurons in the visual cortex of adult mice could indeed reshape the many branches called dendrites that they extend to receive messages from other neurons in a circuit. Lead author Wei-Chung Allen Lee in the lab made pioneering use of new technology, developed with MIT Mechanical Engineering Professor Peter So, for repeated imaging of the same neurons in adult mice over the course of months. Lee was able to document growth and retraction on a fraction of branch tips that were specific to a very particular type of neuron: The changes only occurred in inhibitory GABA-expressing interneurons, and not in excitatory pyramidal neurons where other groups had been looking. The finding led to the hypothesis that adult brains implement plasticity by changing inhibition in circuits.

The lab went on to enrich and test the hypothesis, finding in 2008 that interneuron dendrite remodeling occurred only within a specific “dynamic zone.” Then in 2011 Nedivi’s team showed how this remodeling actually implemented plasticity in response to. For instance, visual deprivation induced dendritic branch retractions, clearing the way for additional remodeling.

Though the work definitively showed that the adult brain retained plasticity in interneurons, the lab nevertheless found in 2018 that this capacity declined with age. Older interneurons showed more and more dendritic retractions and less growth. In a collaboration with Picower Professor Mark Bear, they found that a more youthful balance of growth and retraction could be restored with the antidepressant fluoxetine (Prozac), suggesting a therapeutic value for the drug during brain aging.