The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep continuous track of what’s important to us, even though our visual system’s basic wiring requires mapping what we see on our left in the right side of our brain and what we see on our right in the left side of the brain.

“You need to know where things are in the real world, regardless of where you happen to be looking or how you are oriented at a given moment,” said study lead author Scott Brincat, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Picower Professor Earl Miller, the senior author. “But the representation that your brain gets from the outside world changes every time you move your eyes around.”

In their experiments, Brincat, Miller and co-authors found that when an object switches sides in the field of view, the brain rapidly employs a telltale change in the synchrony of brain wave frequencies to shepherd the memory information from one side of the brain to the other. The transfer, which occurs in mere milliseconds, recruits a new group of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of the opposite brain hemisphere to store the memory. This new ensemble of neurons encodes the object based on its new position, but the brain continues to recognize it as the object that used to be in the other hemisphere’s field of view.

That ability—to remember that something is the same thing no matter how it’s moving around relative to our eyes—is what gives us the freedom to control where we look, Miller said. Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback Tom Brady, for instance, can decide to shift his gaze from the left side of the field to the right side without having to fear that he’ll instantly forget that those left-side receivers are still there, even if changing the gaze position has substantially shifted them within, or even out of, his field of view.

“If you didn’t have that, we would just be simple creatures who could only react to whatever is coming right at us in the environment, that’s all,” Miller said. “But because we can hold things in mind, we can have volitional control over what we do. We don’t have to react to something now, we can save it for later.”

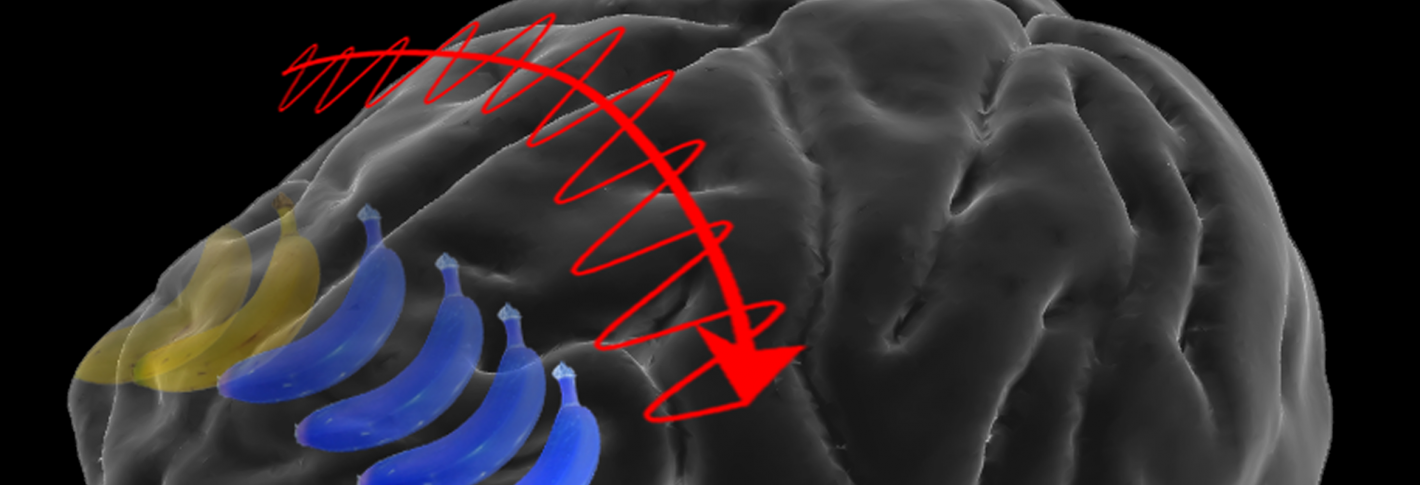

Above: Visual memories transfer from one hemisphere to the other when a mental image shifts across the field of view. Illustration credit: Meredith Mahnke.

Shifting sides

In the lab, the researchers measured the activity of hundreds of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of both brain hemispheres as animals played a game. They had to fix their gaze on one side of a screen as an image of an object (e.g. a banana) appeared briefly in the middle of the screen. The object thus appeared on one or the other side of their field of view, and due to the brain’s crossed wiring, it was processed in the opposite cortical hemisphere. The animal had to hold the image in mind, then indicate if a subsequently presented image was of a different object (e.g. an apple). On some trials, though, while the original object was held in working memory the animals were cued to switch their gaze from one side to the other, effectively changing which side of their field of view the remembered image was on.

Animals were accurate in remembering whether the images they were presented matched, but their performance suffered just a little bit in cases where they had to shift their gaze. Brincat said the error suggests that having to keep up with the shift is not as easy for the brain as it seems.

“It feels trivial to us, but it apparently isn’t,” he said.

To analyze their measurements in the brain, the team trained a computer program called a decoder to identify patterns in the raw data of neural activity that indicated the memory of the object image. As expected, that analysis showed that the brain encoded information about each image in the hemisphere opposite of where it was in the field of view. But more remarkably, it also showed that in cases where the animals shifted their gaze across the screen, neural activity encoding the memory information shifted from one brain hemisphere to the other.

The team also measured the overall rhythms of the neurons’ collective activity, or brain waves. They found that the transfer of a memory from one hemisphere to the other consistently occurred with a signature change in those rhythms. As the transfer occurred, the synchrony across hemispheres of very low frequency “theta” waves (~4-10 Hz) and high frequency “beta” waves (~17-40 Hz) rose and the synchrony of “alpha/beta” waves (~11-17 Hz) declined.

This push-and-pull pattern of rhythms closely resembles one that Miller’s lab has found in many studies of how the cortex employs rhythms to transmit information. Increases in the combination of very low and higher frequency rhythms allows sensory information (i.e. representations of what the animal just saw) to be encoded or recalled. A power increase in the alpha/beta frequency range inhibits that encoding, acting as a sort of gate on sensory information processing.

“This is another form of gating,” Miller said. “This time alpha/beta is gating the memory transfer between hemispheres.”

Spotting a surprise

While the rhythm patterns seemed consistent with prior studies, the researchers were surprised by another finding of the study: Given the same object image in the same spot in the field of view, the prefrontal cortex employed different neurons if it was initially seen at that location vs. transferred from the other hemisphere. In other words, animals seeing a banana in the left side of their vision recruited a different neural ensemble to represent that memory than they did if the banana was previously seen on the right and then transferred to that spot.

To Miller, the finding has an intriguing implication. Neuroscientists once thought that individual neurons were the basic unit of function in the brain and more recently have begun to think that instead ensembles of neurons are. The new findings, however, suggest that even the same information could still be encoded by different, arbitrarily assembled ensembles.

“Perhaps even ensembles aren’t the functional units of the brain,” Miller speculated. “So what is the functional unit of the brain? It’s the computational space that brain network activity creates.”

In addition to Brincat and Miller the paper’s other authors are Jacob Donoghue, Meredith Mahnke, Simon Kornblith and Mikael Lundqvist.

The National Institute of Mental Health, Office of Naval Research, the JPB Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded the research.