General anesthesia is not sleep and sleep is not general anesthesia, but they are both states of unconsciousness and lowered arousal. As a neuroscientist, anesthesiologist and statistician, Emery N. Brown, the Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Medical Engineering and Computational Neuroscience at MIT, has taken a strong interest in understanding and even manipulating the mechanisms underlying such states to investigate “arousal control.” With colleagues he has made several discoveries about how sleep stages can be artificially induced, and anesthesia can be artificially reversed.

Sleep

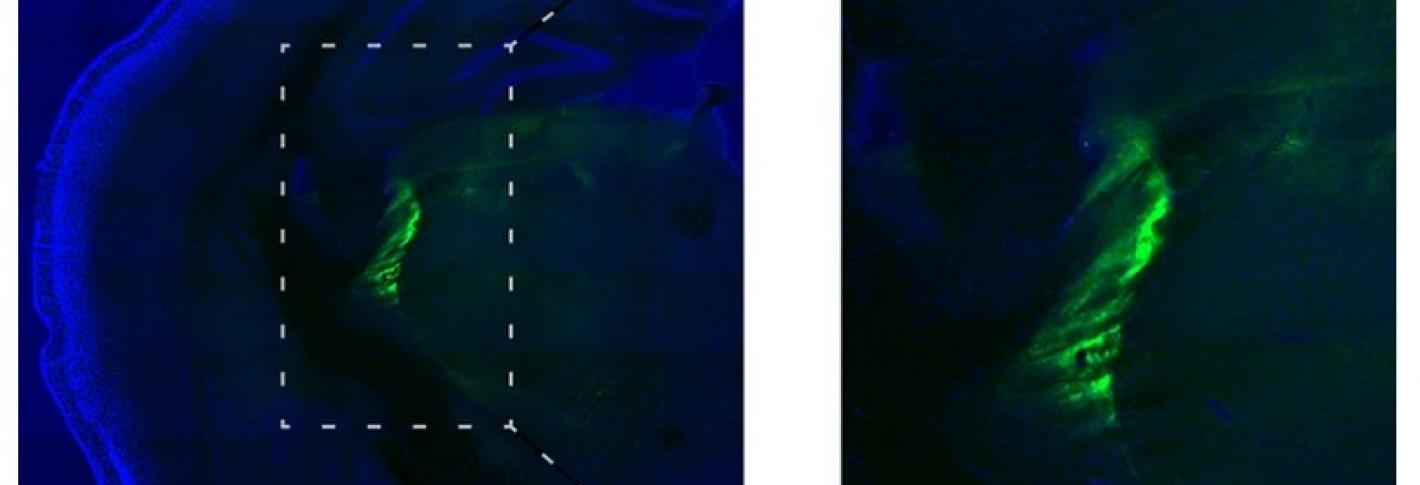

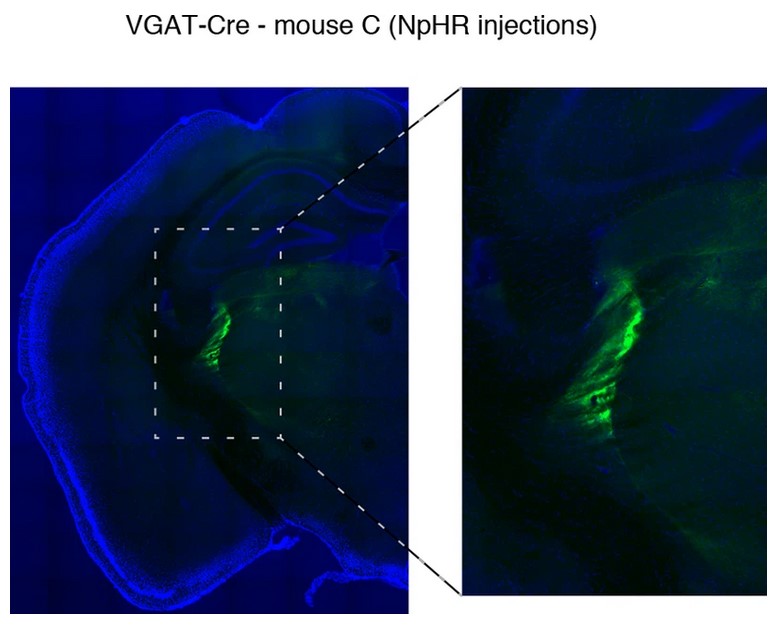

In 2015, the year Brown joined The Picower Institute, he was a senior author on two studies demonstrating circuit mechanisms underlying sleep. In one, he and colleagues showed the key role of brainstem neurons that produce the neuromodulator acetylcholine in the onset of REM sleep. Brown and colleagues engineered mice so that neurons in the pedunculopontine tegmentum and laterodorsal tegmentum regions of the brainstem could be controlled with flashes of light (a technology called “optogenetics”). They used that access to artificially stimulate the neurons. They found that doing so induced REM sleep in the mice. In the other study, Brown worked with Picower Institute colleague Matthew Wilson and Picower affiliate member Michael Halassa, to discover a circuit between the thalamus and cortex that adjusted the arousal of portions of the cortex. They showed using optogenetics that activating the thalamic reticular nucleus led to an increase in inhibition of the thalamus, producing sleep-like slow waves in the cortex. The spatial amount of cortex affected depended on the extent of TRN activation. The study therefore indicated that sleep can be regulated locally or broadly in the cortex.

In 2018 Brown and colleagues induced non-REM stage 3 sleep in people with doses of the anesthetic drug dexmedetomidine. They found that the drug promoted sleep in a manner proportional to dose and did not lead to deficits in cognitive function the way some sedative drugs can.

Arousal from anesthesia

A crucial property of general anesthesia, of course, is that it is reversible. Understanding how people “wake up” is obviously every bit as important as understanding how to put them “under.” Brown’s lab and collaborations has yielded important discoveries about the circuits and brain regions involved.

In 2016 Brown was corresponding author on a study showing that stimulating dopamine-producing neurons on the ventral tegmental area could arouse mice undergoing general anesthesia. The researchers used optogenetics, in which cells can be engineered to be controlled with light, to stimulate the neurons, which woke the mice up.

In 2021 Brown and Picower Institute colleague Earl K. Miller found another way to control emergence from general anesthesia. They were studying how the anesthetic drug propofol works to disrupt coherent brain activity between the thalamus and the cortex. In the study they found that electrically stimulating the thalamus at a very high frequency could undo the effects of propofol, waking up the study’s animal subjects.